Ecuador’s construction of large Chinese-financed hydropower plants over the past decade was expected to rid the country of power shortages and provide surplus power for export to neighbouring countries. But delays, accidents and high costs have left Ecuador struggling to repay its Chinese creditors.

Former president Rafael Correa announced that Ecuador would build eight new hydro plants by 2016 at a total cost of some US$6 billion. Jorge Glas, then minister of strategic sectors, was responsible for the master plan. He was later jailed in 2017 as part of the continent-wide corruption scandal involving Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht.

Only the Odebrecht-built Manduriacu plant was inaugurated on schedule, in 2015. The other seven projects due in 2016 missed deadlines due to engineering and environmental problems. The projects are either partially or wholly owned by Chinese contractors. They’ve been beset with accidents, resulting in the deaths of 26 Ecuadorean and Chinese workers.

Today, only four of those seven projects are operational, providing about 2.5 gigawatts of capacity.

Dams at work

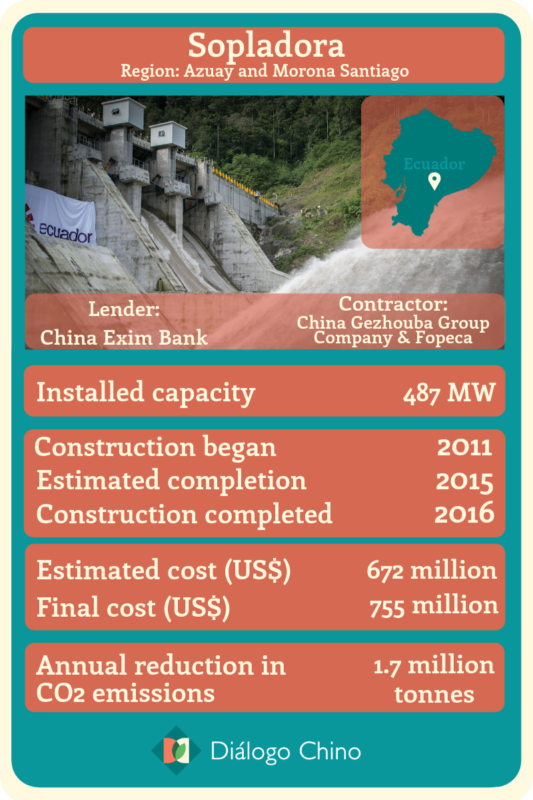

Ecuador depends mostly on coal-fired power but its commitment to increase the share of hydropower, up 35% with the new hydro projects, will allow the country to significantly reduce its carbon emissions.

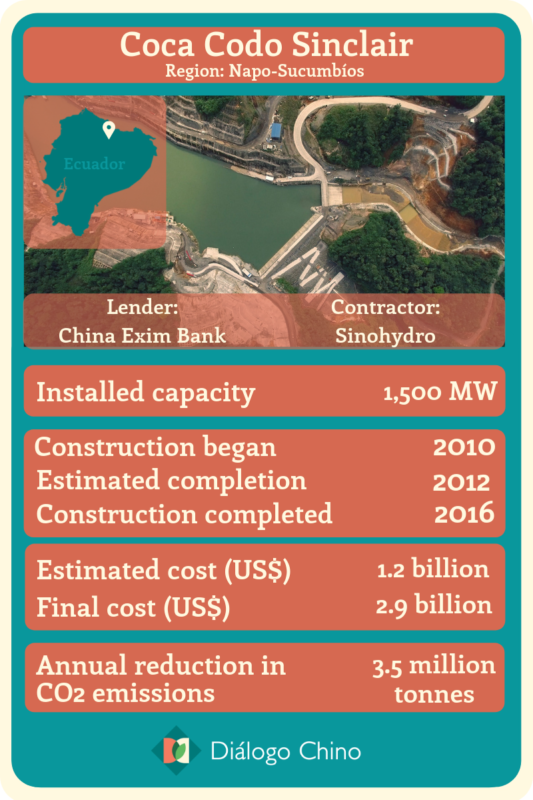

Coca Codo Sinclair, Ecuador’s largest hydroelectric plant, which was due to begin operations in 2012, has experienced financing problems, strikes by workers demanding better conditions from contractor Sinohydro, and accidents such as the December 2014 collapse of a pressure well that claimed 14 lives. The plant, eventually inaugurated at the beginning of 2016, has visible fissures in its water distributors, owing to the use of unsuitable materials, according to a report by the Comptroller’s Office.

Coca Codo Sinclair, Ecuador’s largest hydroelectric plant, which was due to begin operations in 2012, has experienced financing problems, strikes by workers demanding better conditions from contractor Sinohydro, and accidents such as the December 2014 collapse of a pressure well that claimed 14 lives. The plant, eventually inaugurated at the beginning of 2016, has visible fissures in its water distributors, owing to the use of unsuitable materials, according to a report by the Comptroller’s Office.

According to the Electric Corporation of Ecuador (Celec), which will operate the plant, repair work will last approximately one year and the costs will be borne by the contractor. “Ecuador will definitively not take over the plant until all the works permitting Coca Codo Sinclair to operate normally have been carried out,” Celec wrote in an email to Diálogo Chino.

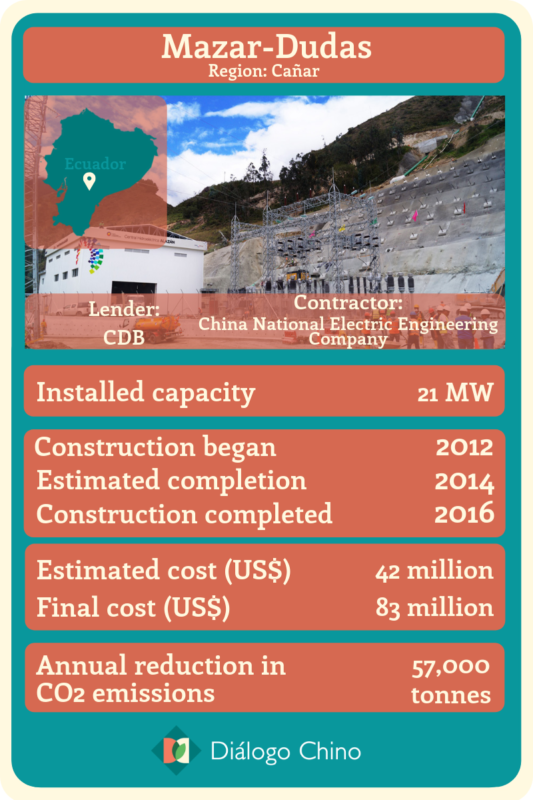

In the case of the three plants that comprise the Mazar Dudas complex, only Alazán is operating. In 2015, Celec unilaterally terminated the construction contract with China National Electric Engineering Company (CNEEC) for non-compliance.

According to the most recent data on Celec’s website, construction of the engine room and the electromechanical assembly of the second San Antonio power plant were planned for 2018. Re-engineering studies for the third Dudas power plant were also scheduled for 2018.

According to the most recent data on Celec’s website, construction of the engine room and the electromechanical assembly of the second San Antonio power plant were planned for 2018. Re-engineering studies for the third Dudas power plant were also scheduled for 2018.

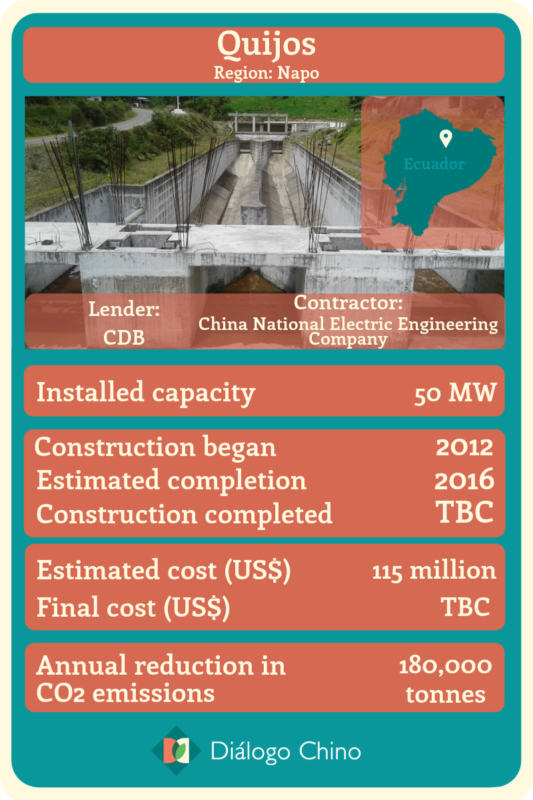

The Quijos project also experienced problems due to CNEEC’s non-compliance with technical standards, according to Celec documents. This led Celec to terminate the contract in December 2015. A mediation process is currently underway between the state attorney’s office and the Chinese firm. In an emergency declaration, Celec ended up awarding the assigning works to local company Proyaben S.A. in 2016 and 2017.

“They couldn’t make any progress as there were geological problems. No matter how many studies you do, the studies are merely superficial,” said Marco Valencia, undersecretary for Electricity Generation and Transmission at Ecuador’s energy ministry.

“Geophysical and geological analyses may be carried out, but the moment you enter with the drilling machinery in hand, you are hit with the reality of the rock itself. In those two projects [Mazar Dudas and Quijos], we encountered geological problems like these, and the contractor could not fulfil their obligations.”

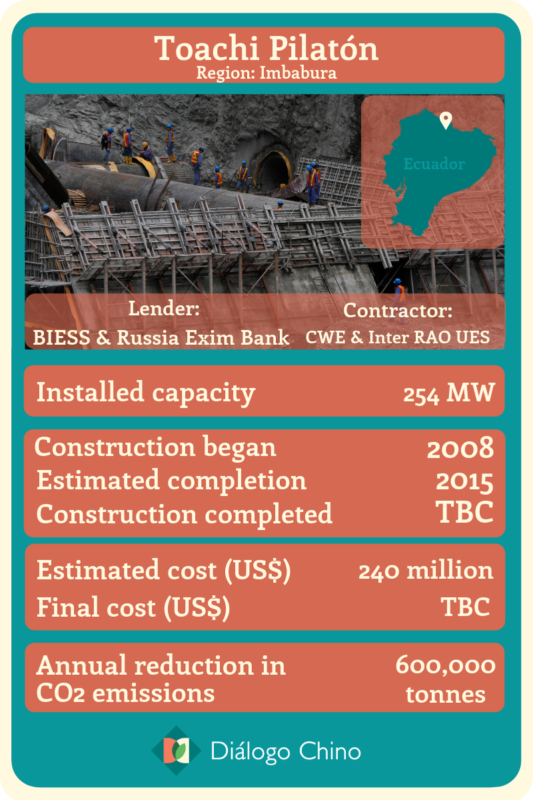

The Toachi Pilatón project is also in a state of paralysis. Construction was ahead of schedule, according to Celec’s 2018 stocktake. In this phase, several foreign companies were involved, including Odebrecht, which was later expelled from the country by the government.

In 2010, Celec hired China International Water & Electric Corporation (CWEC) for the civil construction and the Russian company Inter RAO UES to supply electromechanical equipment.

In 2010, Celec hired China International Water & Electric Corporation (CWEC) for the civil construction and the Russian company Inter RAO UES to supply electromechanical equipment.

Faced with constant delays, Correa ordered the termination of the builders’ contract in December 2016. After one-and-a-half years with no progress, on 22 May 2018 Russian contractor Tyazhmash S.A. was awarded the contract to complete works.

Ecuador’s energy challenges

In 2018, Ecuador produced approximately 23,000 gigawatt hours, most of which powered the country’s homes, industries and public buildings. Hydropower generated 85% of that energy, according to Valencia.

With the new hydroelectric plants in operation, Lenín Moreno’s government has provided assurances that greenhouse gas emissions will be reduced, due to the decrease in the consumption of fossil fuels in thermoelectric plants.

“Since they began operating, each year we have seen a reduction of three million tonnes of carbon dioxide,” Valencia said. According to the undersecretary, in 2014 and 2015 – the years with the highest thermoelectric production – Ecuador emitted an estimated six million tonnes of CO2. In 2016, this fell to five million. This has since dropped to between 1.5 and 2 million tonnes.

However, the overall balance may not be so positive since the construction of hydropower plants has considerable environmental impacts, which, as figures for many of the projects show, also have big economic costs. They have also led to energy overproduction, which is difficult to correct, according to Paulina Garzón of the China-Latin America Sustainable Investment Initiative.

“It’s politically and economically non-viable for any Ecuadorean government to undertake genuinely clean energy projects such as wind or solar when it already has excess energy production and an onerous debt to repay,” said Garzón, who authored a book chapter on the projects and the loans that made them possible. “The construction of Coca Codo Sinclair is an immense obstacle to achieving a truly clean energy matrix in Ecuador,” she added.

Following its loan default in 2008, Ecuador has been locked out of international capital markets, leading Correa’s government to agree loan packages with China that are repaid with oil sales. As global crude prices slumped, Ecuador had to pump more oil to meet its repayments, calling into question both the economic and environmental sustainability of the model.

Following its loan default in 2008, Ecuador has been locked out of international capital markets, leading Correa’s government to agree loan packages with China that are repaid with oil sales. As global crude prices slumped, Ecuador had to pump more oil to meet its repayments, calling into question both the economic and environmental sustainability of the model.

For Arturo Villavicencio, professor of ecological economics and energy at the Andean University, hydropower development was the best way to shift Ecuador’s energy mix, but the scale of development was too great.

“The reasonable thing would have been to select smaller projects, where the national contribution could have been greater,” said Villavicencio, who was also a former member of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“A great opportunity for national technological development was wasted and we would not have had the Chinese making all projects turnkey,” added Villavicencio, in reference to contracts that give decision-making power to the financier.

“A great opportunity for national technological development was wasted and we would not have had the Chinese making all projects turnkey,” added Villavicencio, in reference to contracts that give decision-making power to the financier.

Part of the problem, Villavicencio said, is that many companies were not prepared to sort out the technical problems they found and that the Ecuadorean government has been unable to monitor their work. Furthermore, although there are several construction problems in need of monitoring in the remaining dams, Villavicencio warned that Ecuador will fail to reap the benefits of hydropower if the country does not improve supervision of rivers that feed into the system.

This article is republished from Diálogo Chino