For the public, electric vehicles (EVs) are at the cutting edge of technology and associated with new ideas such as hourly car rentals and autonomous cars. So it’s hard to imagine that some car owners are opting to give them up.

As part of efforts to reduce the number of vehicles on its roads, Beijing started a license plate lottery in 2014. If you want to buy a car, you must first enter and win a license plate. The chance of winning is higher if you apply for a license plate for an EV but despite this many winners end up not making the purchase.

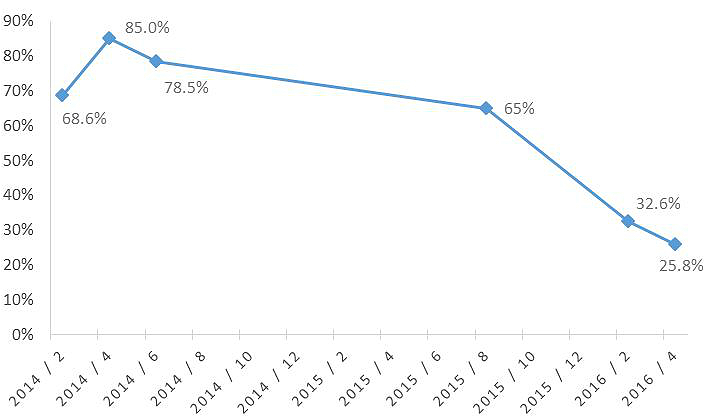

In April 2014, there were 1,904 winners entitled to register an EV but only 286 did so, meaning 85% didn’t take up the opportunity. The situation has improved since then, as the infrastructure EVs need has developed and licenses have sold well – but failure to purchase an EV is still surprisingly common when compared with traditional vehicles.

Percentage of EV lottery winners not making a purchase

Compiled from publicly available data (Feb 2014-Apr 2016) from the Beijing Passenger Vehicle Quota Control Office.

The gap between expectations and reality is due to an ownership experience that often fails to live up to expectations. Behind this lies attempts to rush the development of the EV sector, leading to manufacturers racing ahead of the associated infrastructure. An overall unfriendly user environment means that once potential buyers winning the lottery have weighted the pros and cons, many opt not to make a purchase. There are four main problems: charging difficulties, a poor ownership experience, policy uncertainties, and high prices.

Charging difficulties

For most potential purchasers who win the license plate lottery, the first task is to see if it’s possible to install a charging post next to their parking space at their apartment block. Despite repeated orders from the government to cooperate, property managers are either unfamiliar with government policy or cite safety concerns to refuse such requests. Even if the property managers are cooperative, the process involves installation, planning and an electricity supply – it’s a time consuming and troublesome task, and one that some potential owners spend six months on before giving up.

Also, the salaried classes which are the biggest source of demand for EVs struggle to afford private parking spaces, which are hugely expensive. The number of public charging posts is increasing, but there are problems here too – compatibility across different suppliers, long queues, and parking fees incurred while charging. In 2014, the city’s development and reform authorities promised to build 1,000 public charging points – a promise that was not fulfilled. These issues mean potential purchasers lack confidence.

A poor experience

The experience of driving an EV is another concern. With battery capacity and therefore range still limited, there’s little spare power for other uses. In particular, drivers may not be able to use the air conditioning to keep warm in winter and cool in summer – turning driving into an ordeal. Almost all drivers of EV taxis don’t dare use the air conditioning, even in the depths of Beijing’s harsh winters. That’s hard to take for anyone used to driving a petrol vehicle. Decreasing range as batteries age is also a major issue. And more dangerously, there have been media reports of a BAIC E150 EV being driven normally during a test drive suddenly decelerating without warning from 80 km/h to 40 km/h.

Policy changes

EVs still rely on government assistance to be competitive and so uncertainty over government policy has a huge impact on purchases. First, buyers have to opt for a vehicle on a specific list of promoted vehicles if they are to benefit from certain policies but this reduces an already narrow range of choices even further. They also have to puzzle over why local government lists differ widely from those issued by central government, and buyers often give up as they can’t purchase the model they want. Policy also changes too quickly. An exemption from a 10% consumption tax for purchases of EVs is a good idea, but its sudden announcement left those who had bought an EV before the new policy came into effect feeling they’d lost out.

High prices

Despite various subsidies, an EV still costs more than the equivalent petrol-fuelled model. A 20% reduction in state EV subsidies on 2016 levels has pushed prices higher again. Also, running costs aren’t genuinely lower than traditional cars, particularly if drivers use commercial charging stations, where a cost of two yuan per kWh is giving rise to affordability complaints. Add in parking fees while charging, queuing, and the time lost while recharging, and EVs are no money-saver.

EVs also depreciate rapidly even when subsidies are accounted for. A five or six year old EV is worth only 20% of the purchase price, compared to 40% for a conventional vehicle.

EVs cannot rely on a glamorous aura. It is essential to increase the quality of the vehicles and improve the ownership experience. Also, given the limited results obtained by single-mindedly promoting electric-only vehicles, other mature clean vehicle technologies such as natural-gas, methanol and hydrogen fuel cells should be considered as back-up alternatives for reducing China’s transportation pollution problem.

Originally published on the CBN Research website, republished with permission