Editor’s Note: At the recent World Ocean Summit in Bali, we caught up with Beth Lowell, Oceana’s senior campaign director and author of new report No More Hiding at Sea: Transshipping Exposed.

China Dialogue: What is transshipping?

Beth Lowell: Transshipping is the transfer of cargo, fuel, provisions, crew, gear or fish catch from one vessel to another, and can take place in port or at sea. Although these events are often legal, restrictions on transshipment of fish vary by a country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), flag state and region.

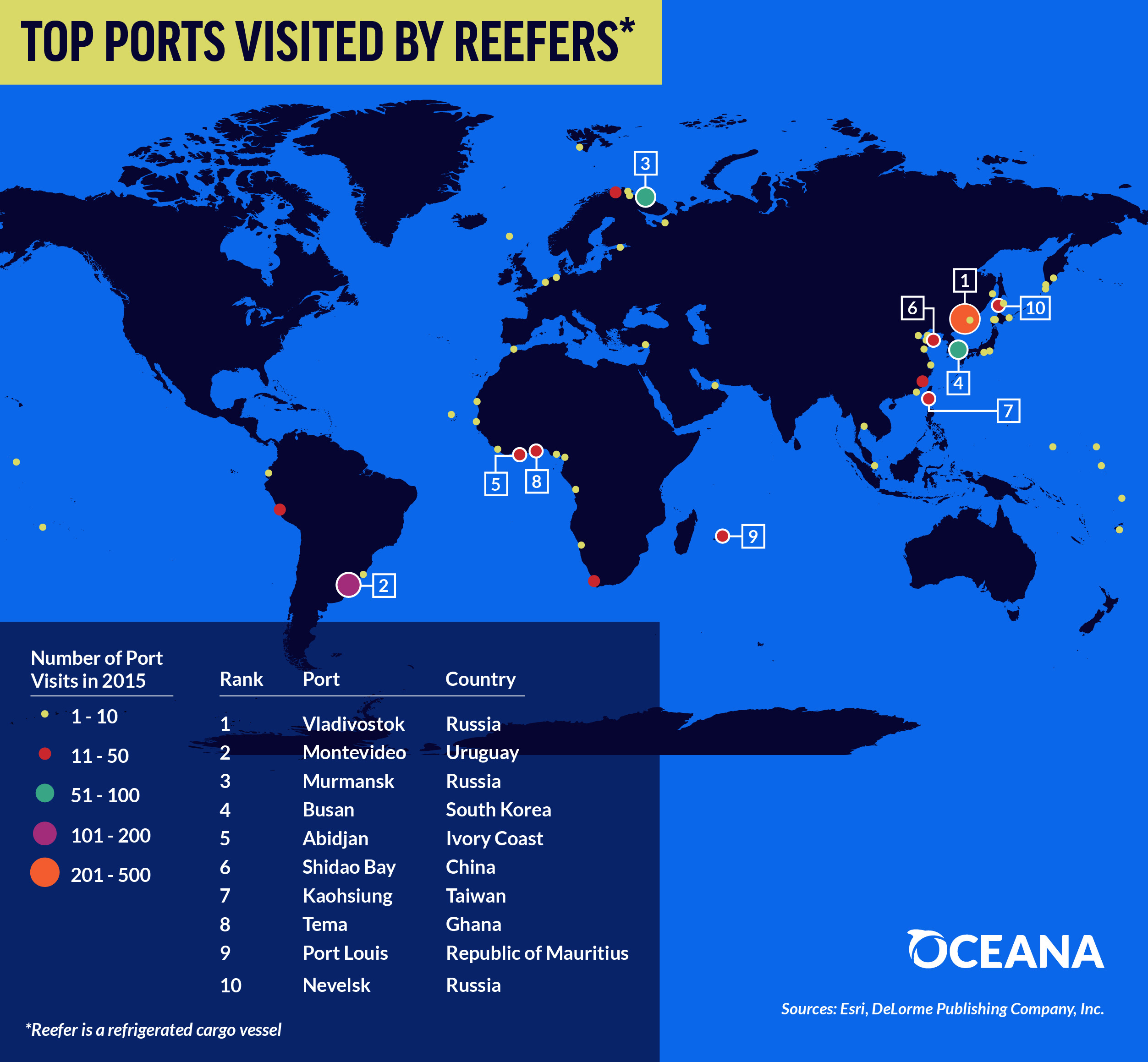

Often, transshipment occurs between a fishing vessel and a refrigerated cargo vessel, also termed a “reefer,” and can facilitate illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing by enabling vessels to transfer their fish catch far from ports and hidden from fisheries managers.

Transshipment can be a way for bad actors to get away with illegal and unscrupulous practices far from the eyes of authorities.

CD: If it is a legal practice then why does it pose a serious environmental and human rights threat?

BL: Transshipping can have profound impacts on the management and sustainability of fisheries resources. Reefers are built to rendezvous with multiple fishing vessels, combining each vessel’s catch in large refrigerated holds for storage before landing the accumulated catch in port. This practice can facilitate illegal fish laundering, where illegally caught fish is mixed with legally caught fish and then sold as such.

Likewise, reefers are not always inspected upon arrival in port and can be exempt from providing catch documentation, hindering seafood traceability and transparency. Weak regulatory frameworks allow transshipment to occur at sea without verification of catches or monitoring for potential transnational criminal activities.

Transshipping also allows fishing vessels to remain at sea for months to more than a year, which not only undermines the ability of management organizations to monitor and control high-seas fisheries, but also increases the potential for suspicious behaviors like illegal fishing and human rights abuses.

IUU fishing depletes the world’s oceans and can gravely affect small-scale fisheries by exploiting coastal waters on which they depend, especially in developing and small-island nations with insufficient resources to adequately police their EEZs.

Unregulated fishing has also been linked to other organized, transnational crimes at sea, including human trafficking, smuggling of migrants, forced labor and drug trafficking.

CD: The report identifies transshipping hot spots. Where are these emerging and what countries own the vessels involved in suspected rendezvous?

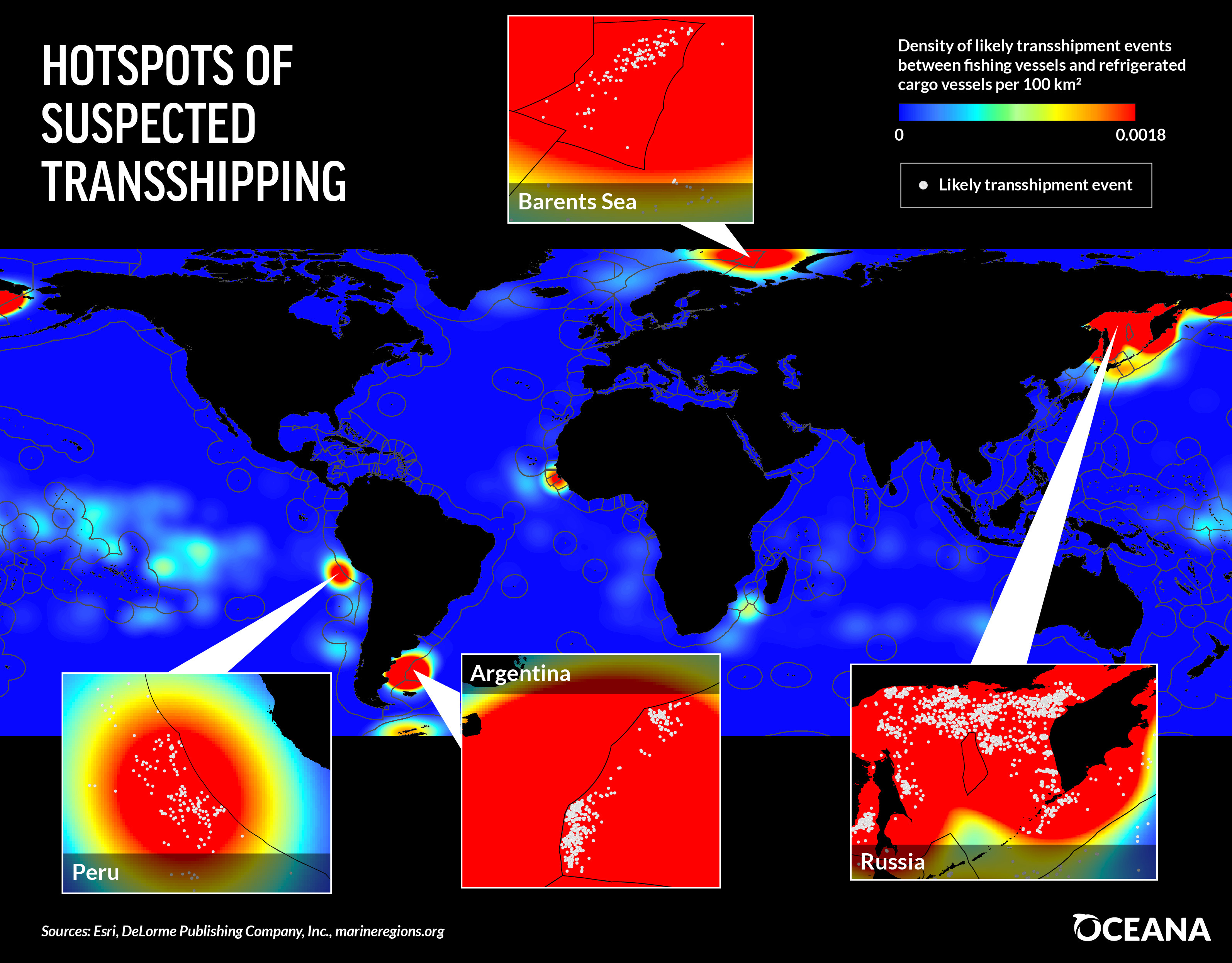

BL: Our report presents a global view of likely transshipping hotspots from 2012 to 2016. These events represent 5,065 suspected rendezvous between 282 reefers and 965 fishing vessels.

High-density regions are in Russia’s Sea of Okhotsk, outside the EEZ of Argentina, outside the EEZ of Peru and the Barents Sea Loophole, a high-seas region surrounded by the EEZs of Norway and Russia.

More than 60% were detected in national waters, with Russian waters containing half of all likely transshipping events.

After Russia, several nations including Kiribati and Guinea-Bissau accounted for 9% of likely transshipments in national waters.

This suggests that small island nations and developing countries that have limited resources or ability to monitor and enforce their national waters may be more vulnerable to at-sea transshipping.

In the Southern Ocean, 3% of events occurred in the Bransfield Strait, where Antarctic krill are commercially fished under the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, and Japanese waters contained another 3 % of the likely events.

Our analysis showed that in 2016, Russian-flagged fishing vessels ranked highest for the average number of suspected rendezvous per vessel in a national fleet.

Comoros and Vanuatu, both flag of convenience countries (based on a list compiled by the International Transport Workers Federation), were the second and third highest-ranked countries using the same metric. (A flag of convenience is when a vessel pays a fee to register under the flag of a different country, and can allow fishers to avoid their own country’s regulations.)

CD: How many transshipping incidents are estimated to take place every year and how much fish is illegally fished?

BL: Data released by SkyTruth and Global Fishing Watch (the product of a partnership between Oceana, SkyTruth and Google) identified 5,065 likely rendezvous of refrigerated cargo vessels with the largest commercial fishing vessels between 2012 and 2016.

We suspect that transshipping at sea, occurring out of the eyes of the port inspectors, is where some illegally caught fish is entering the supply chain.

According to global estimates, a minimum of 20% of seafood worldwide is caught illegally, representing economic losses between US$10 to US$23 billion and 11 to 25 million metric tons of fish.

CD: What will happen if this practice is not tackled and whose responsibility is it to do so?

BL: If transshipping at sea is not tackled, fishing vessels can continue to transfer their catch at sea, beyond the eyes of fisheries managers. Governments and management bodies need to know how much seafood we are taking out of the oceans in order to set scientifically based catch limits to ensure that we have seafood for the future. The oceans cannot be properly managed without accurate catch reporting and monitoring. Transshipment at sea is a roadblock to transparency at sea.

CD: How is technology being used to prevent this practice?

BL: Increasing transparency of global commercial fishing is key to responsible fisheries management. Large fishing vessels are required to carry and transmit Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals.

Public platforms like Global Fishing Watch now allow anyone with internet to monitor commercial fishing vessels that are equipped with AIS and track their activity in near real-time. This is made possible because satellites and terrestrial receivers collect AIS information and Global Fishing Watch uses this information to track vessel movement and classify it as “fishing” or “non-fishing” activity.

CD: What is the first step that regulators should take?

BL: Governments and those responsible for managing fisheries around the world should:

-

Ban transshipment at sea: A ban should be implemented on a global scale, through RFMOs and coastal states’ national jurisdictions. Transshipment activities should be strictly regulated and only take place in ports.

-

Mandate vessel tracking: Require all fishing vessels to carry and transmit AIS or other comparable, publicly available tracking systems.

-

Require unique identifiers for fishing vessels: Unique vessel identifiers, such as IMO numbers, increase the transparency of the global fishing fleet, as these numbers remain with the vessel through changes in ownership and flags.

-

Adopt global catch documentation schemes: Consistent catch reporting will provide regulatory certainty for fishing industry members while facilitating information-sharing and coordinated global efforts to stop IUU fishing.