Editor's Note: This is the first part of a new chinadialogue blog series examining developments around America's energy and climate policy under the Trump Administration as they unfold.

President Trump may want to withdraw the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement, but California, the most populous US state, is intent on pushing ahead with significant climate legislation regardless.

In August 2016, the California Legislature set a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by more than 40% below today’s levels by 2030. Last month, in July, there was a vote on extending a cap and trade programme, a crucial mechanism to achieving this target.

The programme works by setting a limit on the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted annually. This cap then declines each year. Polluters that fall within the programme, such as energy providers and manufacturers, can buy and trade permits to emit greenhouse gases. If the programme works it should lead to economically efficient emissions reductions.

Governor Jerry Brown didn’t mince his words before the vote when he told legislators: “this is the most important vote of your lives,” and tweeted:

“This isn't about some cockamamie legacy. This isn't for me, I'm going to be dead. It's for you and it's damn real.”

The legislation passed, with the help of eight Republican votes; a rare and encouraging sign of bipartisan support for climate action.

Size matters

California’s economy is enormous and so its actions are not just limited inside the state. It has a GDP of US$2.4 trillion, more than twice that of Guangdong province. Its cap and trade scheme will be the second largest in the world, behind only the European Union. The state is also a hub for high-tech, low-carbon innovation, including Tesla Motors, a manufacturer of highly desirable electric vehicles, and Beyond Meat, a start-up that aims to “perfectly replace animal protein with plant protein”.

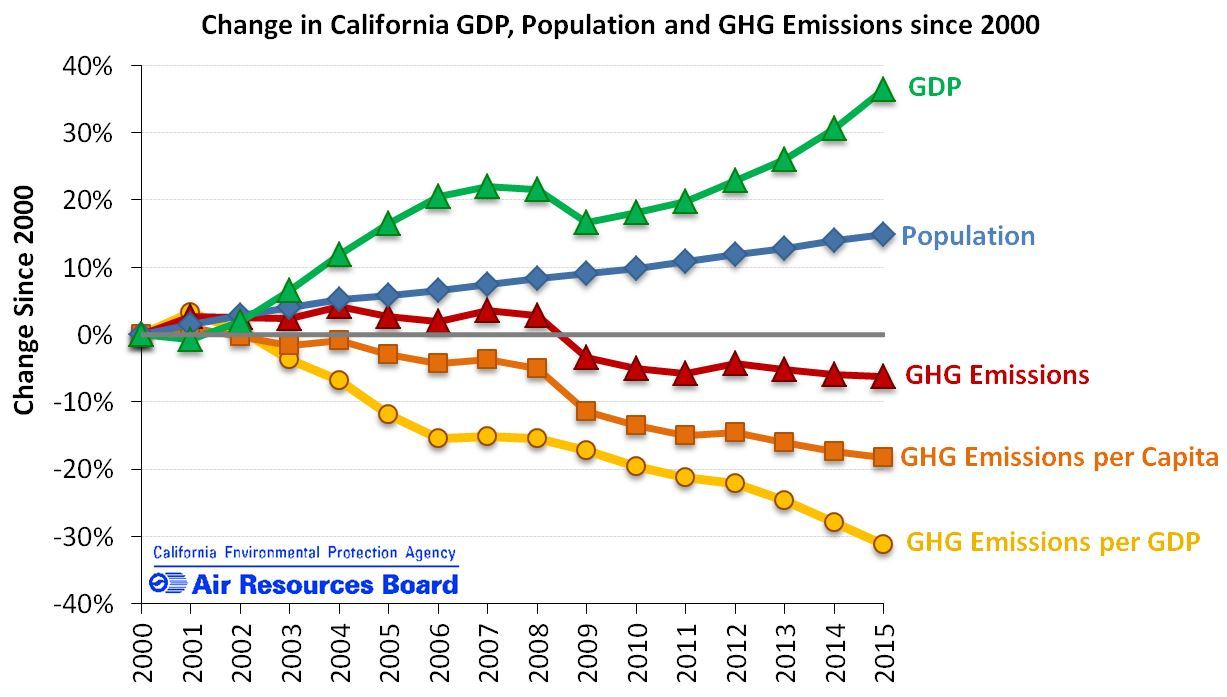

Thanks to this combination of innovation and strong climate policies, greenhouse gas emissions in the state have declined since the early 2000s, even as the economy has grown rapidly. These reductions have been largely concentrated in the electricity sector, which has seen huge growth in low-carbon energy. California now has as many solar panels as the rest of the country combined.

But emissions from transportation, which make up over a third of the current total, present a trickier problem. To meet the state’s 2030 targets, Californians will need to electrify everything they can, starting with cars. The state has already spent US$695 million on low-carbon transportation. Ambitious new public transport schemes, including a high-speed rail link between San Francisco and Los Angeles, will not be cheap either.

Getting the cap and trade scheme to work well will be critical. The legislation means the programme will operate until 2030, with the amount of greenhouse gases companies can emit to fall 40% by this date. Businesses can buy credits in auctions if they require higher greenhouse gas emissions and the funds are used to accelerate climate action. In practice, the supply of permits has often been too generous, resulting in a low carbon price.

Political compromise

President Trump may also have something to say here. While the American political system grants states significant powers, the federal government can, for example, change fuel economy standards for vehicles at the national level. This would reduce incentives for car makers to manufacture more fuel efficient or electric vehicles, and potentially clog California’s roads with old-fashioned gas-guzzlers.

Gaining bipartisan support for the legislation has also required compromises. For example, local government agencies are blocked from establishing rules to limit greenhouse gases, and efforts to improve air quality in areas that house oil refineries will likely suffer as a result. Some environmental groups are sceptical that cap and trade can deliver the scale of reductions needed. Miya Yoshitani of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network said the bill “gives unacceptable concessions to the oil industry, and impedes our ability to clean our air, improve our economy and to protect Californians.”

A lot is riding on cap and trade in California. If the scheme fails, sceptics of climate action will have another reason to delay. Although nine states in the Northeast have their own carbon trading system, the idea has been slow to catch on in the rest of the country. The number of states taking action must rise if the US is to help the world avoid dangerous climate change.

Global leadership

In the meantime, Governor Brown has become a de facto leader for the United States, reassuring the world that some citizens take climate commitments seriously. He recently met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and California’s cap and trade scheme has been studied by Chinese experts. There is even talk that the two may be linked in future, though that’s likely to be a long way off.

Governor Brown may have been well received in China, but other American leaders have been less receptive. Brown recently chided Florida Governor Rick Scott, a Republican, for having “his head in the sand” on climate; Scott famously banned state officials from even using the term climate change, despite the climate risks that Florida faces. Californian politics, on economic and social issues as well as the environment, are also more liberal than most other states, which may limit Brown's ability to get other states to follow.

California’s political leadership on climate is a positive sign in a difficult time, but in the end economics may play a more important role. A combination of Chinese manufacturing and US finance has driven the cost of wind power to record lows in Texas, which now produces more energy from wind farms than any other state in the country, even though Texas has no significant climate or clean energy policies.

Of course, truly transformative change requires both political leadership and economic incentives. California now has both. America and the rest of the world will be watching closely.