Unlike your everyday consumer rubbish, electronics waste is especially challenging to deal with because it contains a range of hazardous substances. The world produced 41.8 million tonnes of waste electronics (e-waste) in 2014, according to the United Nations University’s 2014 Global E-Waste Monitor. Of that, six million tonnes, or 14.3%, was produced in China.

Take mobile phones as an example of the e-waste challenge. Data from the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology shows that China shipped in 560 million mobile devices in 2016. Industry insiders estimate that between 400 to 500 million mobiles could be discarded in favour of new handsets annually in China in coming years. And this is on top of the one billion mobiles already dumped in the country.

China’s e-waste industry is in for an upgrade though. In January, the State Council released a document calling for an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system. By the end of 2017, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and other government bodies must put forward a proposal for recycling of electric (devices that use electricity, such as fridges, hairdriers and microwaves) and electronic products (devices that alter electric currents internally using switches, such as computers or mobile phones).

And this is just the start. By 2025, the State Council wants to see an EPR system in place for key product types, “major advances” in environmental product design, and for at least half of discarded products to be reclaimed and recycled.

Manufacturer responsibilities

To do this, the proposed EPR system establishes four areas of manufacturer responsibility: producing environmentally-friendly designs, using recycled materials, standardising waste management and recycling processes, and disclosing data on recycling. The first two areas seek to reduce the environmental footprint of products at source whereas the second two push manufacturers to take responsibility for tracking and reusing products throughout their respective lifecycles.

Tong Xin is a professor at Peking University’s College of Urban and Environmental Sciences who studies EPR systems. She told chinadialogue that waste management has never been the sole responsibility of the Ministry of Environmental Protection before. The new approach is designed to overcome the problem of divided and overlapping responsibilities across multiple government bodies because under the new system all aspects of the industrial chain will be held responsible, and manufacturers are a key player in those chains.

To begin with, the EPR system will focus on four product types: electric and electronic products, cars, lead-acid batteries, and drinks packaging.

Inevitably, this will mean increased costs for manufacturers in these sectors, which is a major concern for them, says Du Huanzheng, a professor at the UN Environment, Tongji Institute of Environment for Sustainable Development. The extra costs from recycling are expected to be passed onto consumers through higher prices.

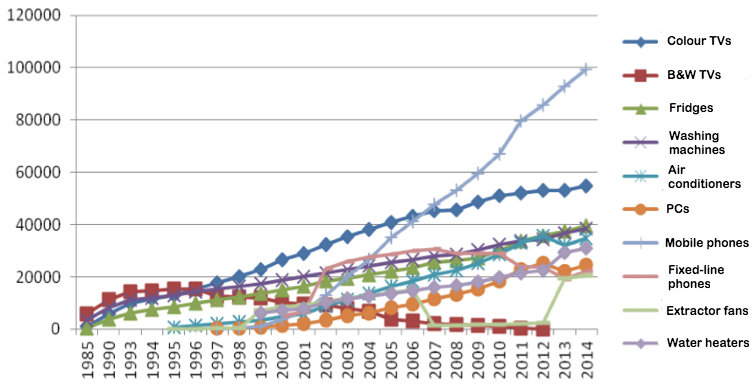

Quantities of domestic appliances owned by Chinese households (10,000s)

Source: China Household Electric Appliance Research Institute (CHEARI), White Paper on WEEE Recycling Industry in China 2015

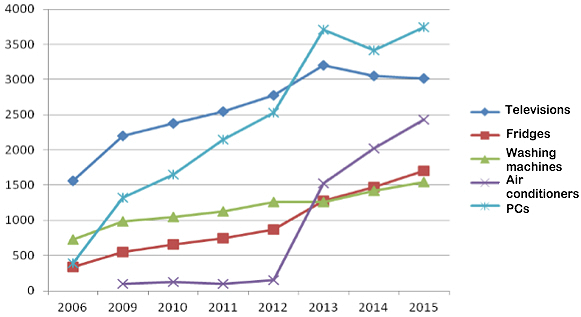

Theoretical quantities of appliances discarded annually, 2006-2015 (10,000s)

Source CHEARI, White Paper on WEEE Recycling Industry in China 2015

What’s new about the EPR?

The new EPR system aims to improve the current recycling system for electronic products that dates to 2008 or after. This is when China issued the Circular Economy Promotion Law to reduce consumption of resources and creation of waste in manufacturing, logistics and consumption, and to make manufacturers responsible for the lifecycle environmental footprint of their products. However, no practical rules for implementation of the law were put in place.

In 2009 regulations were issued for the recycling and disposal of discarded electric and electronic products, including a list of products covered, a fund for disposal of electronic products, and licensing for firms handling the waste. These rules are still in place today but they only apply to recycling and disposal, meaning there’s no effort to improve design and manufacturing.

The new EPR system tries to put this right. It’s the first attempt regulate across the entire product lifecycle – from selection of materials, to design, to recycling and disposal.

The EPR system also encourages more formal methods of electronics recycling. It proposes online recycling channels to make it easier for consumers to access formal recycling, rather than simply discarding electronics or selling them to informal recyclers.

The system also aims to combine market mechanisms with recycling, creating a new recycling channel that suits consumer habits. There are already several online recycling platforms that are experimenting with formal market-based models such as Xiangjiaopi, Alahb, Huishouge, and Aihuishou.

The informal recycling sector

The government wants to promote greater use of the formal recycling sector because currently the bulk of electronic waste is handled by informal recyclers. According to a survey by CHEARI the informal sector handled 86% of China’s electronic waste in 2015.

One of the problems with this is that low-value components may be discarded incorrectly, resulting in secondary pollution and environmental damage. Workers have no labour, health and safety protections either, leaving them especially vulnerable. But it is these failures that make the informal sector so competitive.

The government has imposed strict licensing and limits on the number of waste firms in the formal sector – currently the Ministry of Environmental Protection has licensed only 109 companies. But several experts told chinadialogue that large quantities of discarded products are snapped up by small scale workshops and traders, leaving nothing left for larger firms, meaning such facilities lie idle.

Li Boyang is deputy head of the Energy Saving and Environmental Protection Research Centre at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s China Electronics and Information Industry Development Research Institute (CCIDWise).

Li told chinadialogue that licensed disposal firms require production lines that meet national environment standards, and which use suitable technology to dismantle, discard and reuse waste, all whilst providing basic protections for employees. This means a single production line can cost tens of million yuan – leaving these firms at a huge disadvantage compared to smaller and more flexible informal traders.

Although the electronic product disposal fund subsidies formal recyclers, those subsidies are issued quarterly and can be late, sometimes by as much as a year.

Li Boyang admits that it is difficult to regulate and manage the informal recycling sector, which is why the government hopes to direct as much electronic waste into the formal sector as possible. But individual waste-pickers do play an important role in keeping cities clean. However, this group is overlooked by the EPR system, which will only affect formal manufacturers and recyclers.

Tong Xin indicated that the relationship between the informal and formal sectors is difficult for the government. If the informal sector is not brought under control there is no point in building up the formal sector, as it will not obtain any waste. However, taking jobs away from the informal sector will be just as diffucult.